Brazil needs to reconnect its rail network , but is attempting to do so in an election year, with a regulatory model in transition and a fragmented infrastructure.

For this reason, the year began with a dilemma at the Ministry of Transport regarding the National Railway Concession Policy, announced in November 2025. The project portfolio foresees eight auctions in 2026, covering more than 9,000 kilometers (km) of track and with the potential to attract up to R$ 140 billion in private investment.

The challenge, however, goes beyond the tight schedule. The new railway policy seeks to address the structural problem of Brazilian logistics: the fragmentation of the network, marked by thousands of kilometers of idle tracks, low integration between concessions , and the need to create regional connections – a role that is now being assigned to so-called shortlines.

Today, rail transport accounts for about 27% of freight movement in the country, while road transport accounts for 62%, a model that has reached its economic and physical limits.

“There is no other option but to continue investing in railways. Brazilian road transport has reached its limit,” says Paulo Resende , coordinator of the infrastructure and logistics center at the Dom Cabral Foundation.

According to him, the increase in exports of soybeans, corn, pulp, and bulk goods puts pressure on a system designed for short distances. "Road transporters will suffer a drop in revenue if they have to expand long-distance transport of these cargoes to the ports," he adds.

In addition to the loss of efficiency, there is a direct impact on public assets. To compensate for the small scale, trucking companies have increased the capacity of their trucks, accelerating the wear and tear on highways. As a result, the cost of infrastructure assets has jumped to about 23% of GDP, compared to 12% ten years ago.

This logistical urgency helps explain a recent irony in the transportation sector and the "breakdown" of a typically national practice. Amid political polarization, the concessions agenda has begun to follow a logic of continuity between governments of different political spectrums.

After differing experiences since the 1990s - from high tolls to the so-called "social toll" of Lula's first government - the economic model prevailed.

“The format began to give way during Dilma's government, advanced with Temer, and was buried during Bolsonaro's government. In the current PT administration, it ceased to be questioned and became the rule,” says Resende.

The Fernão Dias Highway symbolizes this turning point. The last survivor of the social toll system, it operated with a toll of R$ 3.20 per axle. In the new concession, the value will exceed R$ 10, after the concessionaire was unable to sustain the previous model.

This consensus explains why, regardless of the outcome of the 2026 elections, the sector expects the current models to be maintained from 2027 onwards, even if part of the current agenda is abandoned.

Regulatory vacuum

The impact of the election calendar is already apparent in attempts to negotiate eight railway assets. The renegotiation of the Ferrovia Centro-Atlântica (FCA), the country's largest concession, is at risk after the government admitted the possibility of temporarily extending VLI 's contract to avoid a regulatory vacuum.

The concession expires in August. The agreement provides for the renewal of 4,138 km, the return of 3,082 km of abandoned track, and an investment of R$ 28 billion over 30 years. "The renewal is at an impasse, with disagreements over the agreed-upon compensations," states Urubatan Silva Tupinambá Filho, a railway expert.

Other projects will have to wait. The Ferrogrão railway, spanning 933 km and estimated to cost R$ 20 billion, still lacks environmental licensing and approval from the TCU (Federal Court of Accounts). "Although excellent logistically, it faces significant socio-environmental obstacles," says Tupinambá.

There are also obstacles in the re-bidding process. The Malha Oeste (1,625 km between São Paulo and Mato Grosso do Sul) had its return reevaluated after new pulp projects, while the Malha Sul , whose contract expires in 2027, is likely to be divided into three auctions in the next administration.

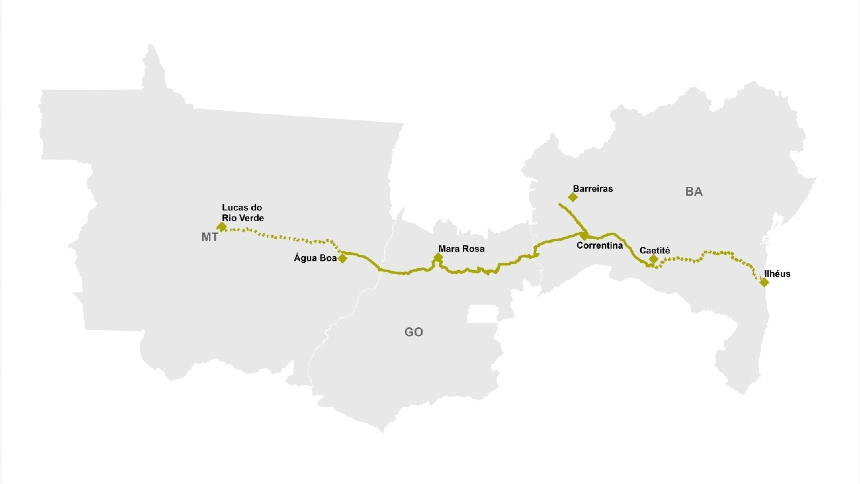

The Fico-Fiol corridor, spanning approximately 2,700 km, is the government's main focus. Fiol 1 could be incorporated into the project given the limitations of the current concessionaire, Bamin. The interest of Mota-Engil – associated with the Chinese company CCCC – has rekindled the possibility of completing the Porto Sul project in Ilhéus (BA).

Among the initiatives with the best chance of moving forward are the EF-188 , a 575 km greenfield railway between Rio de Janeiro and Espírito Santo, and the Minas-Rio Corridor, whose auction is scheduled for April 2026.

The project will be structured through a public call for proposals – a hybrid model that seeks to reactivate idle sections through PPPs, with economic subsidies, simplified licensing, and fewer regulatory obligations.

Since 2021, the National Land Transport Agency (ANTT) has received 108 requests for railway authorization. Just over 40 have been granted, and only half a dozen are close to becoming a reality, generally supported by large grain, pulp and bulk cargo groups.

Despite the extensive portfolio, experts question the government's ability to meet the schedule in an election year.

According to Daniela Poli Vlavianos, a partner at Poli Advogados, there is no legal impediment to holding auctions during this period. The challenge is institutional. "Effectiveness depends on regulatory stability and the predictability of administrative decisions."

Marcus Quintella , director of FGV Transporte, is more skeptical. For him, the viability of the projects depends on identifying demand – an inexact science – and the legal security of the right of way.

He cites the case of Galeão Airport in Rio de Janeiro as an example of flawed projections that resulted in financial losses. Quintella also points to legal uncertainty regarding the right of way as a central obstacle.

"The trunk railways, controlled by large concessionaires such as VLI, Rumo and Vale, do not guarantee access, tariff clarity or interoperability," says the expert.

"The absence of a functional open access model discourages new investments, as investors depend on third parties to connect to the main network," he adds.

According to the TCU (Brazilian Federal Court of Accounts), the country has 30,653 km of railway tracks, of which approximately 19,000 km are idle. Even with new models, many of these sections would require significant investments before operation.

Still, Paulo Resende, from the Dom Cabral Foundation, sees room for progress. “The regulatory framework for authorizations is well established, and the projects are simpler than concessions and renegotiations,” he says. “There is an expectation of acceleration, including as a political showcase.”

Between traditional concessions, shortlines, and new regulatory models, the country's challenge remains the same: to transform disconnected rail lines into a network capable of sustaining export growth and reducing Brazilian logistics costs, regardless of who occupies the presidency next year.