“I wanted to write you a very long letter, in which we could discuss 'Constructive Art' and your very interesting book, La tradición del hombre abstracto . This long and detailed letter is not possible for me to write today, nor in the coming days. I am busy with all sorts of work. But, upon receiving this letter of yours, with its sweet spiritual camaraderie, I want to at least offer you a few words of thanks.”

This is how the letter that the poet Cecília Meireles addressed, on April 8, 1939, to the Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres-García begins. The letter opens the exhibition Joaquín Torres-García: 150 years , on display at the Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil , in São Paulo, and presents itself as a key to understanding the show, which explores connections, not always evident, between the artist and Brazilian art.

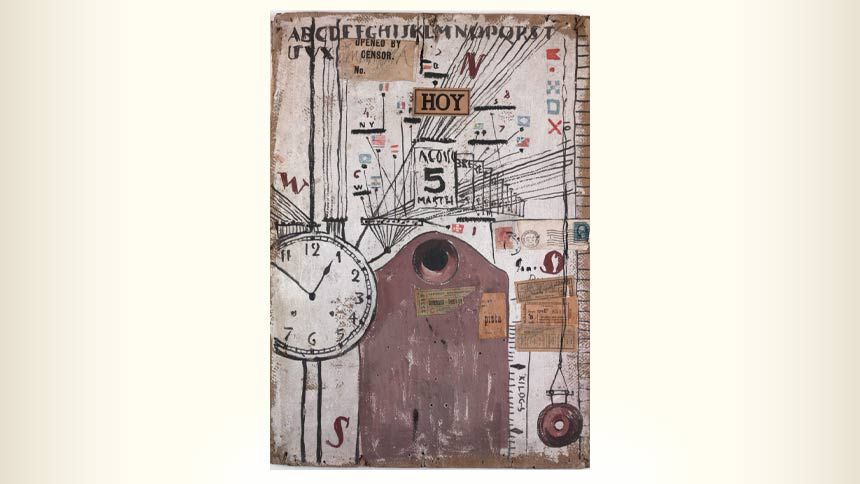

The exhibition brings together around 500 items, including works by Brazilian artists, paintings, unpublished manuscripts, drawings, and wooden toys produced by the Uruguayan artist. There are no lengthy wall texts or explanatory captions.

A discreet timeline, positioned at the bottom of the page and surrounding the exhibition rooms, offers only the essentials of Torres-García's chronology. According to curator Saulo Di Castro, the choice was not to assume the role of interpreter, but to create conditions for the artist himself to speak for himself.

“I had the chance to interact with historical artists and I knew that Torres-García’s story is often viewed in a stereotypical way,” Di Castro states in an interview with NeoFeed . “He is much more important than he seems—including for the discussion about the relationship between image and word, which predates concrete poetry.”

Although he traveled through Brazil and wrote about the country, Torres-García is not usually among the most immediate references for Brazilian artists.

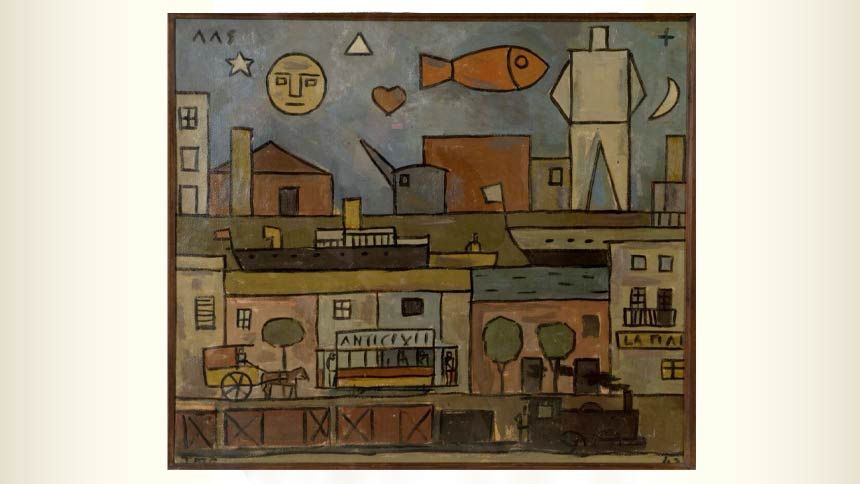

Perhaps for this reason, at first glance, the juxtaposition of his early paintings with ancestral Peruvian ceramics and works by artists such as Ernesto Neto and Willys de Castro may seem arbitrary.

The curatorial approach, however, is to provoke the visitor, inviting them to go beyond merely semantic connections and to make an active effort to see, an idea present in Torres-García's thinking.

“Quite unlike the literary type, the true artist does not know things in a concrete way, but has already seen them,” the artist wrote in Writings on Art .

"Archaeology of the future"

Di Castro explains that the presence of Ernesto Neto, for example, acts as a turning point. The Brazilian artist is heir to a constructive tradition that passes, in particular, through Lygia Clark , who never separated formal rigor and sensory experience.

His textile sculpture, the curator states, “softens the rigorous structure that concretism carried,” shifting it to the realm of touch and synesthetic experience. “Neto establishes a profound dialogue between sculpture and painting, because the sculpture is made of fabric—a derivation of the painting medium,” he explains.

According to Di Castro, this same logic extends to the relationship with Peruvian ceramics, whose millennial temporality echoes in Torres-García's research. The Uruguayan artist studied ancestral peoples in search of a universal geometry that could be rearticulated in his work.

“I tried to speak by placing myself in the position Torres-García occupied,” says the curator. “He identified symbolisms from different civilizations and incorporated them into his work. Strangely, by delving so deeply into the past, he ended up producing something that resembles a kind of archaeology of the future.”

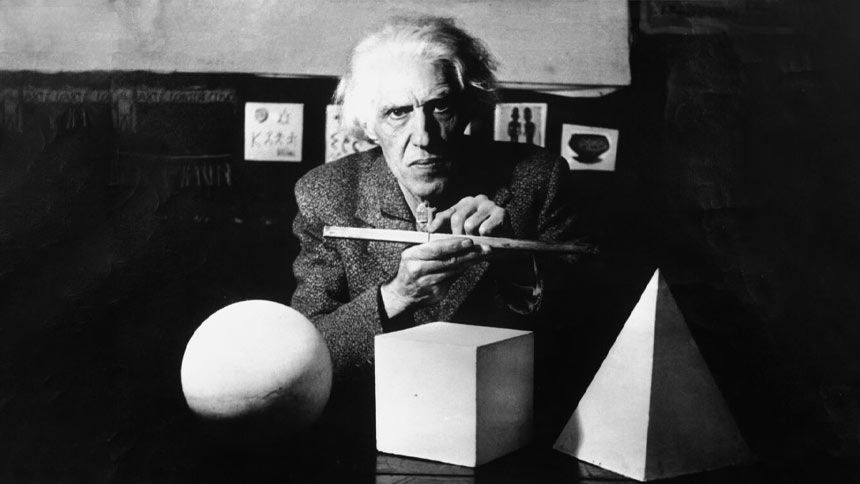

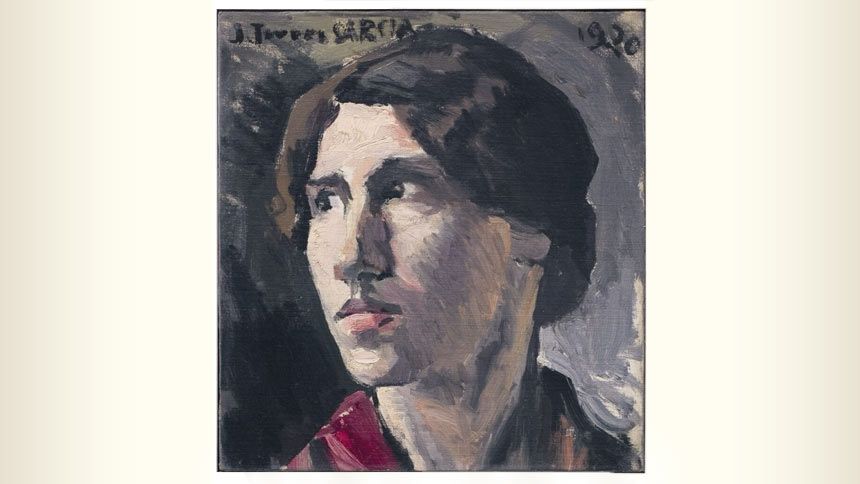

The son of Spanish immigrants, Joaquín Torres-García was born in Uruguay in 1874. At the age of 17, he moved with his family to Barcelona, separating them from their homeland for about four decades. In 1920, he went to the United States with his wife Manolita Piña and their children.

Faced with the difficulty of supporting his family solely through the sale of his artwork, he founded the Aladdin Toy Co. in New York in 1924, dedicated to the manufacture and distribution of wooden toys that he had been developing for years.

However, the following year, a fire destroyed the factory and halted production. This event, in retrospect, almost seems like a warning for the artist to refocus definitively on his work.

Fire, moreover, reappears as a recurring tragedy surrounding his work. In 1936, six large murals painted in the Spanish chapel of the Blessed Sacrament in the Church of San Agustín in 1908 were destroyed in a fire.

Almost thirty years after his death, in 1978, during a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro , a fire in the building destroyed about eighty of his works.

“He was the most fiery artist in history,” the curator recalls. “That fire has a flame of life. As if, in Torres-García’s story, there was a complementarity between opposing forces with which he grappled.”

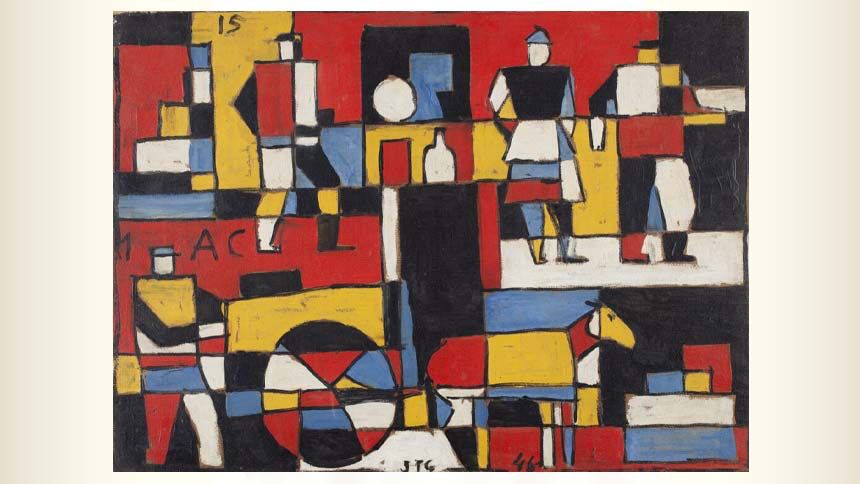

After coming into contact with Piet Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg, and the members of the neoplasticism movement during one of his stays in Paris, Torres-García developed his own poetics. From constructivism, he incorporated geometric forms, primary colors, and the black line, but organized them into a unique graphic style and vocabulary.

It was in Uruguay, after his return in 1934, that the artist—distant from the avant-garde and the European past—managed to put his most celebrated project into practice: "to build a whole world: a popular art, in which the highest and most universal is expressed in a simpler and, therefore, more personal language," he wrote.

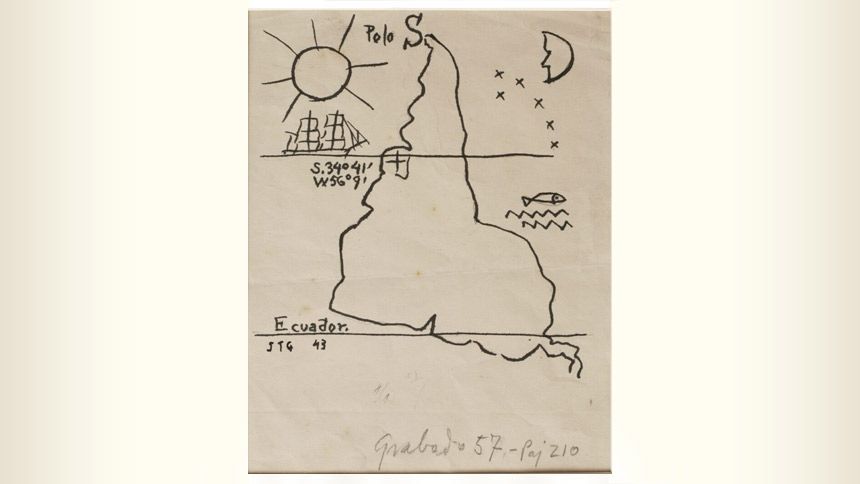

Perhaps the ultimate symbol of this desire is the small drawing "Inverted America ," in which the Latin American continent appears upside down, asserting that its north was the south.

“Inverted America is a cosmological arrow,” Di Castro summarizes. “It stands there as a great universal work of art because it teaches us values of unity and calls for similarities to be more important than differences, which generate conflict.”