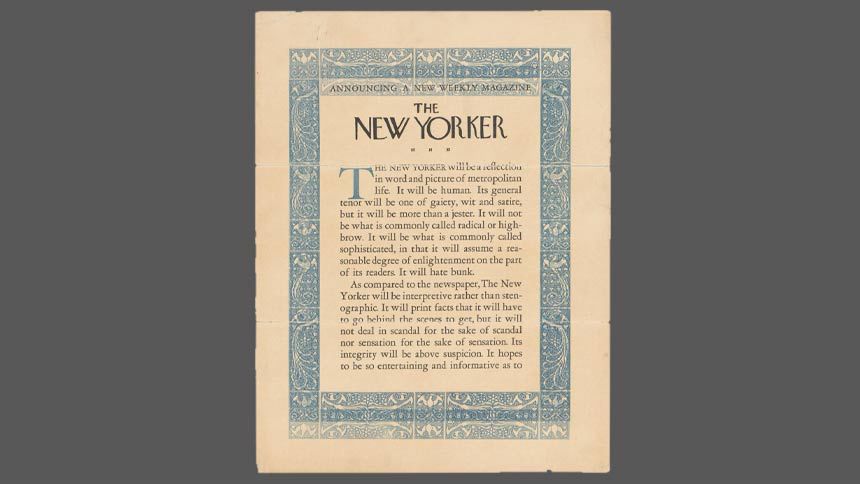

New York – “ The New Yorker will be a reflection in word and image on metropolitan life. It will be human. Its general tone will be one of joy, insight, and satire, but it will be more than playful. Compared to newspapers, the magazine will be interpretive rather than stenographic.”

Thus begin the two pages that outline the mission of the weekly magazine created in 1925 by the journalist couple Howard Ross and Jane Grant. The document is one of the framed pieces in the commemorative exhibition A Century of The New Yorker , celebrating 100 years of The New Yorker, on display until February 21, 2026, at the majestic headquarters of the New York Public Library in Manhattan.

No other place would make more sense: the library holds more than 2,600 boxes of original articles, letters, cartoons, and illustrations from the 5,057 issues published throughout the century. The magazine produces about 47 volumes a year, and any true New Yorker knows they pile up in corners of the house, given that the texts are longer than the time available to read them all.

In addition to the exhibition, the anniversary was celebrated with a recently released Netflix documentary, in which filmmakers Marshall Curry and Judd Apatow infiltrated the newsroom for months, participating in editorial decisions, reporting, fact-checking, and interviewing the stars behind the city's—or even the country's—most iconic magazine.

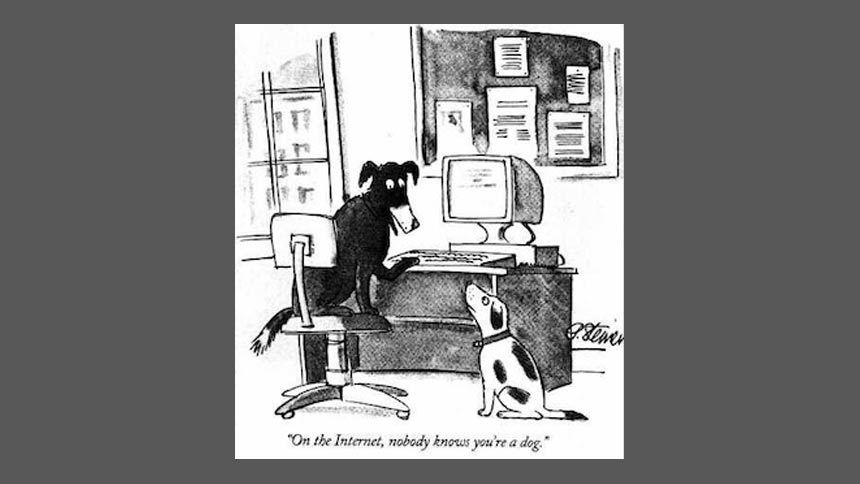

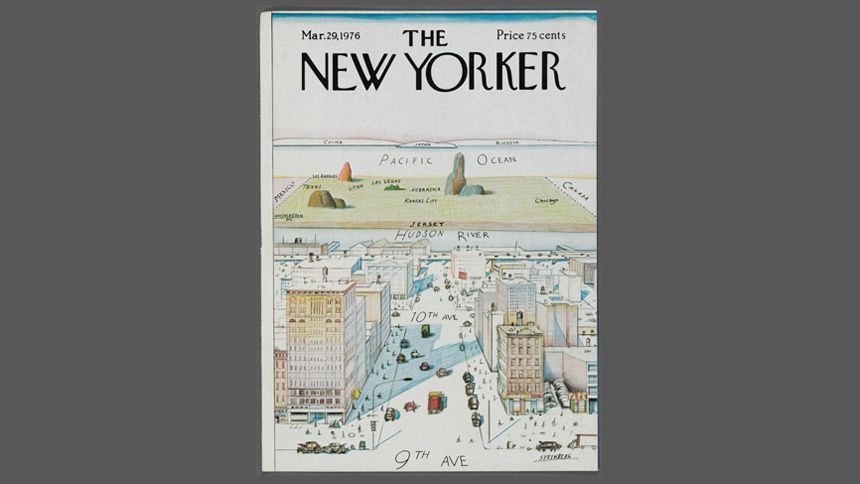

“In a single week, The New Yorker publishes a fifteen-thousand-word profile of a musician or a nine-thousand-word account of southern Lebanon, with cartoons interspersed throughout the text. There’s never a photograph on the cover, no one in a bikini, or a movie star. And yet, it works,” says editor-in-chief David Remnick in the film. “The fact that this format exists and thrives is impressive. And I insist: it will continue to thrive not for a century, but for two or three.”

At 67 years old, and with a career that includes books and a Pulitzer Prize, Remnick has held the position since 1998, being the fifth in line since the magazine's creation.

He was lured away from The Washington Post by then-editor Tina Brown, who was hired at the time to revitalize the magazine: in addition to fresh blood, she brought innovations such as photography to the pages.

But in its early years, The New Yorker wasn't all that great. So much so that, in 1928, one of the magazine's most prominent writers, E.B. White, considered leaving.

Soon after, he received a telegram (seen in this exhibit) from the founder that read: “This is a movement, and you can’t quit a movement.” E.B. White stayed and became one of the most respected writers in the country. And in 1949 he would publish the legendary essay Here is New York (not for the magazine), as well as a writing manual respected to this day and the children's book Charlotte's Web .

"Hiroshima"

Throughout its hundred-year history, The New Yorker has grown in relevance by never abandoning its principle of recruiting the best. The exhibition clearly demonstrates how quality and meticulousness come first and how the publication has gradually embraced diversity, both in its coverage and in its hiring of writers.

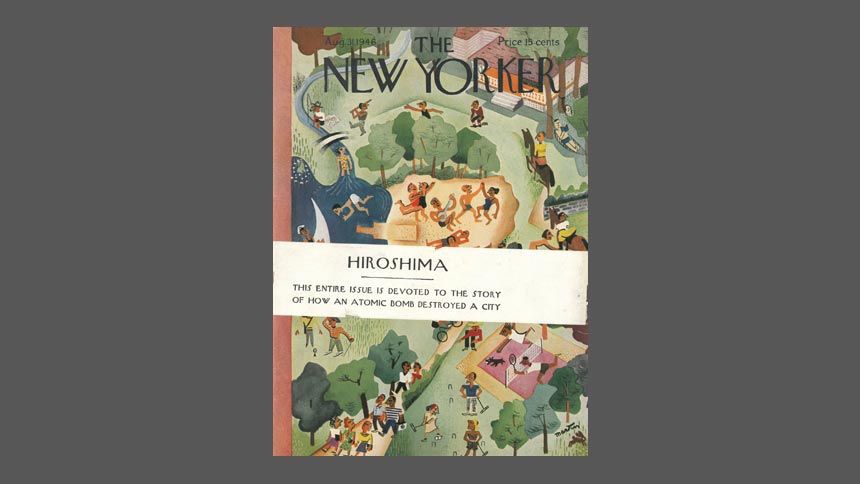

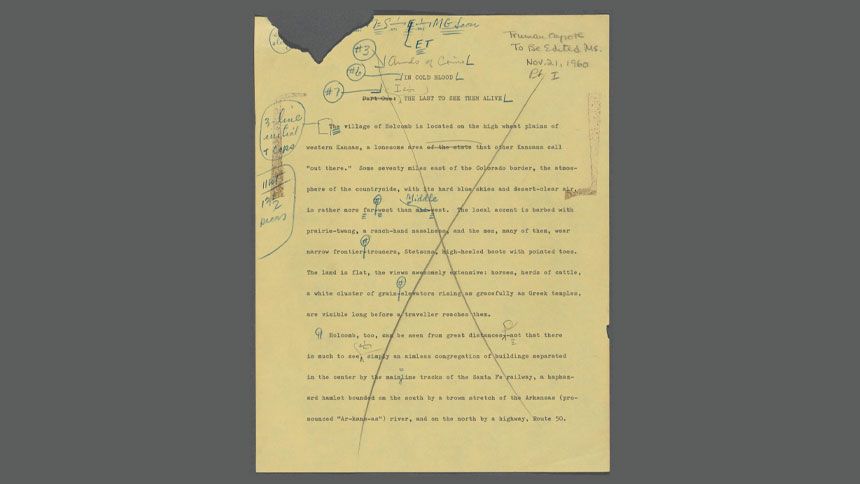

In the 1940s, one of its reports finally earned the magazine the journalistic recognition it deserved by addressing a major wound: Hiroshima.

At the time, the national media did not report on the effects of the bomb, but journalist John Hersey went there and brought the story of six people who lived through the terror. On August 31, 1946, for 15 cents a copy, The New Yorker hit newsstands with the title: Hiroshima: This issue is entirely dedicated to telling how an atomic bomb destroyed a city . The cover illustration showed a (formerly) happy community. Albert Einstein ordered a thousand copies.

The topics are decided in editorial meetings, and after the text is submitted, it goes to the fact-checking department, where 27 heroes check every detail, calling sources, reading files, verifying dates — “a process compared to a colonoscopy,” as they joke in the documentary. After that, the text undergoes a grammatical check, where no misplaced comma or redundant word goes unnoticed.

Today, The New Yorker costs US$9.99 and charges a subscription to read it online (US$52 for the first year, and US$130 annually from the second year onwards). At its founding, Howard Ross, who at the time secured investment to get it started, said that the magazine would be dedicated to "a sophisticated Manhattan audience, and not to the old lady in Dubuque" (a tiny town in Iowa).

Ross, who didn't even finish school and was born in a mining town in Colorado, handpicked his friends: he knew who was capable of developing irreverent articles and cartoons about local society and culture.

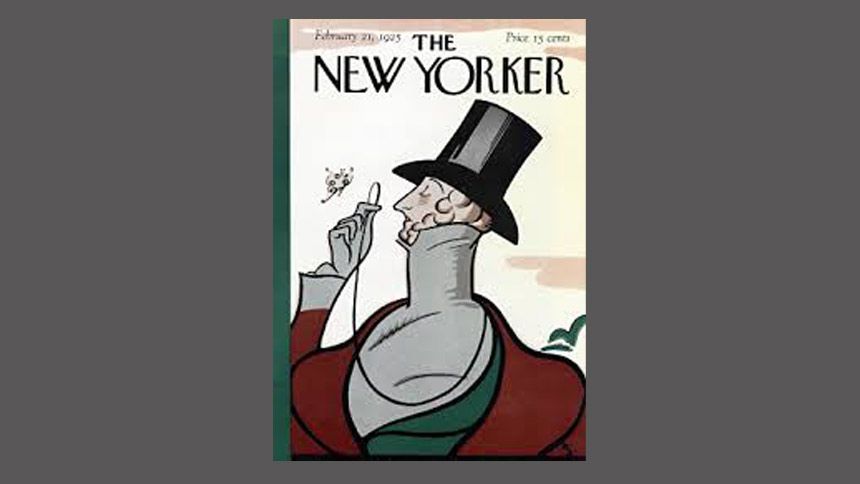

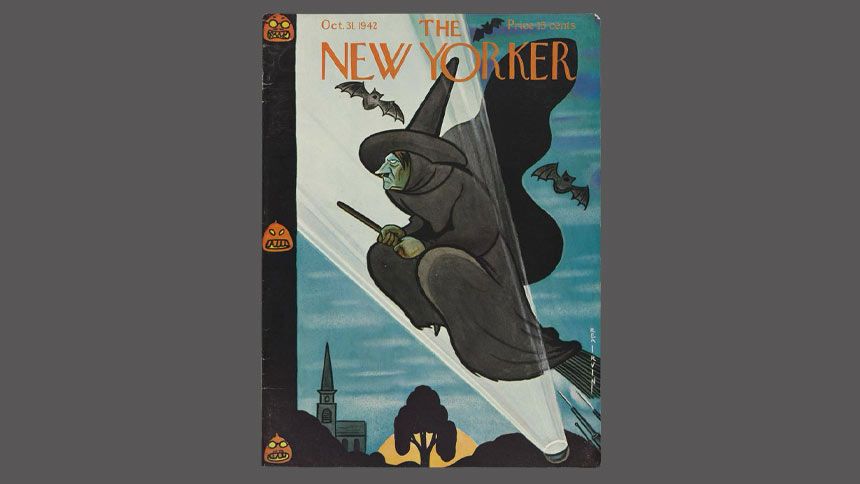

Furthermore, he brought Rea Irving, the designer who created the typography and the first cover: the iconic character gazing at a butterfly through a monocle. The original illustration, also on display in the exhibition, is a satire of the magazine's tone: Eustace is a sophisticated name and Tilley, a mundane surname.

Originally used as a pseudonym in humorous texts, Eustace Tilley became the publication's mascot, with reinterpretations in each anniversary edition: new characters, in the same profile position, looking at the butterfly.

A Brazilian cover

“Until we choose the cover, we don’t know what the personality of the edition will be. The cover needs to speak to the moment, but also be a timeless piece of art that can be framed and hung on the wall,” says art director Françoise Mouly in the documentary.

Having held the position for 30 years, she was responsible for historic covers, such as the two twin towers in black after September 11th and the commemorative cover for the 100th anniversary, which rewarded readers with six options: in addition to the republication of the original page, she selected the reinterpretation of Eustace made by five different artists.

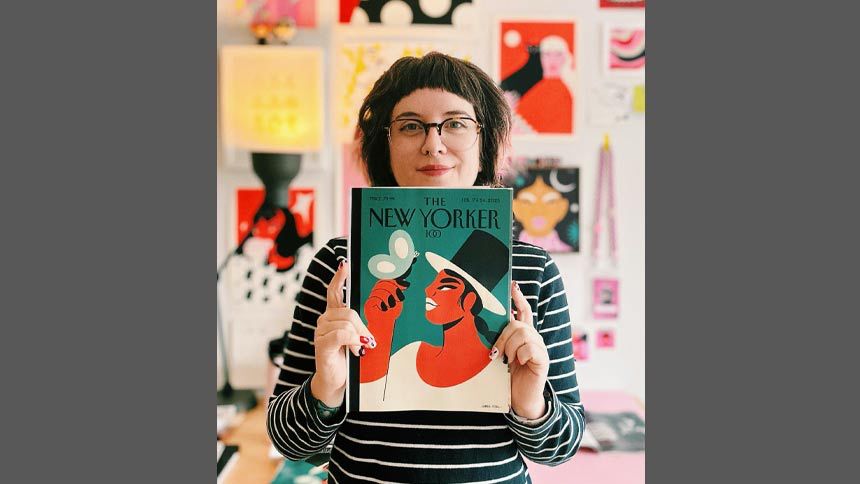

Among them, a surprise: the profile of a woman with Latin features, illustrated by Brazilian Camila Rosa, 37, born in Joinville and based in Brooklyn.

“In January 2023, Françoise contacted me about a possible commemorative cover for the 98th anniversary. She asked for ideas focused on reinterpretations of the original 1925 cover,” Camila tells NeoFeed .

“With this proposal, I came to understand the tradition and weight of this character. I always wanted to illustrate the magazine, but I had never immersed myself in this universe. Because, yes, it is a universe that is part of the life of a New Yorker,” he adds.

Camila submitted two sketches, including one of a Latina woman. But at the time, the illustration wasn't published. In any case, the submissions are kept in an idea bank, which is constantly revisited.

Last November, Françoise contacted the Brazilian again, this time asking for a colored and finished version of the sketch she had submitted two years earlier.

“I presented some color options and awaited a decision. There is a waiting period because both the covers and the articles are not necessarily planned for the next edition. It can take years,” he explains.

The connection came last January, when Françoise announced that Camila's cover would appear in the 100th-anniversary commemorative edition, coming in February.

“Being on the cover of The New Yorker would already have been a milestone in my career. But participating in the centennial edition was beyond anything I could have imagined,” she says.

"My work has taken on a new dimension, especially because of the relevance of bringing this topic to the cover amidst the current political context of the country," he adds.