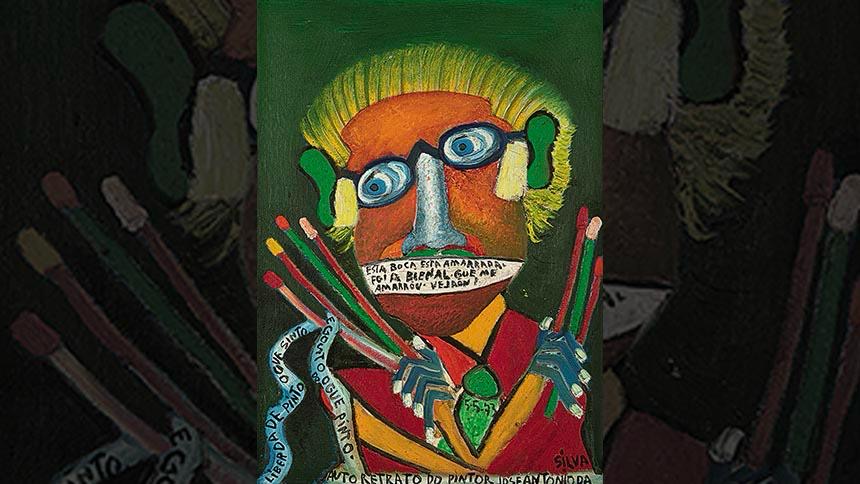

In a self-portrait, José Antônio da Silva paints himself with brushes firmly in his hands and, over his face, places a kind of gag on which he writes the accusation: “this mouth is tied, it was the Biennial that tied me up. Look!”.

In another, men in suits—direct allusions to Brazilian art critics—hang from a beam against a dark background, while, at the top of the scene, Christ raises his arms and commands: “Go to hell.” The images do not call for reconciliation. They announce an artist who never treated the art system as neutral ground.

Painting Brazil , an exhibition currently on display at the Museum of Contemporary Art of USP, curated by Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro, stems from this direct confrontation. After circulating at the Grenoble Museum in France and the Iberê Camargo Foundation in Porto Alegre, the show brings together works that present this artist who never doubted where his work should be.

“Silva built his career in a very conscious way,” says Fernanda Pitta, professor and curator at MAC-USP, who also participated in the exhibition's setup. “These self-portraits show not only the figure of the artist, but someone who grapples with his own environment, fully aware of the challenges of asserting himself within it.”

Silva's recognition followed a rapid and unlikely path. Born in 1909 in Sales Oliveira, about fifty kilometers from São José do Rio Preto, he had little formal education and worked as a farm laborer before dedicating himself to the arts. Self-taught, he moved to São José do Rio Preto in 1931.

Fifteen years later, in 1946, he participated in the inaugural exhibition of the city's House of Culture, where his paintings caught the attention of critics such as Lourival Gomes Machado and Paulo Mendes de Almeida, as well as the philosopher João Cruz Costa – important names in the São Paulo art scene who dictated what deserved to be seen.

From that exhibition to the invitation to the first edition of the São Paulo Biennial in 1951, it was a quick step. Throughout his career, Silva established strategic relationships with key figures in the art world.

Among them is the collaboration with the industrialist and patron Ciccillo Matarazzo, who allegedly gifted businessman Nelson Rockefeller with a work by the artist – a gesture interpreted as an attempt to appease the artist's discontent at not having received the Biennial's top prize, which he believed he deserved.

This closeness, however, has never been without tension. "When these critics don't respond in the way expected, he objects, he speaks out. And when thwarted, he reacts," the curator points out.

Modern and popular

Paying close attention to what he saw in art exhibitions, he ventured into pointillism throughout the 1950s. Instead of constructing the image exclusively from the pointillist technique, as tradition prescribed, he applied a layer of dots over an already structured painting, creating a texture. The procedure appears in works such as Still Life in Pointillism (1951) and Portrait of my wife Rosinha (1957).

“Silva was absorbed by this artistic milieu as an artist who was, in quotation marks, primitive, naive,” says Pitta. The critical reception to these experiments outside this framework was not always good – which did little to dissuade him. “He reacts by claiming the formal freedom granted to modern artists, but rarely offered to an artist classified as popular,” he adds.

Aware of the mechanisms of legitimation within the art system and attentive to controlling his own narrative, Silva invested in strategies used by the art world. In Romance de minha vida (1949), he wrote about his own life trajectory, anticipating interpretations and disputes surrounding his work and life.

In 1966, he created the Municipal Museum of Contemporary Art of São José do Rio Preto, after having already founded a space dedicated exclusively to his work. The initiative was not naive. Observing the workings of the São Paulo art scene, he understood that, to remain visible—and inscribed in the history of art—it would be necessary to build his own institutions.

I am Silva.

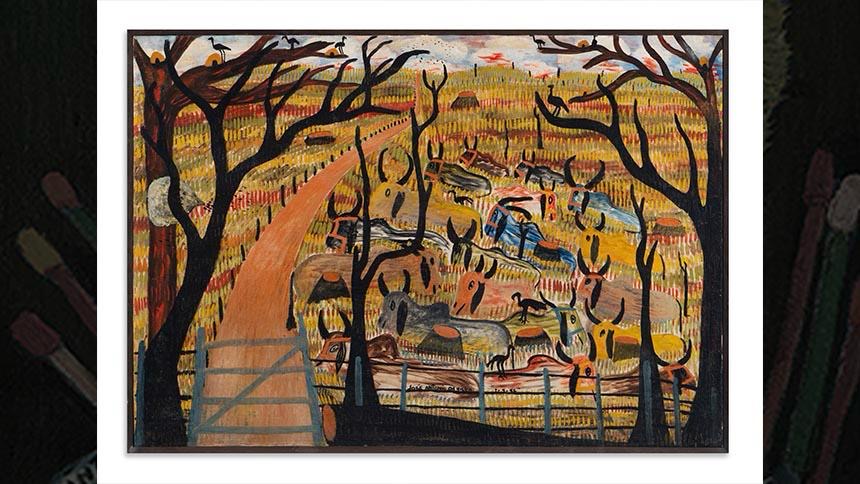

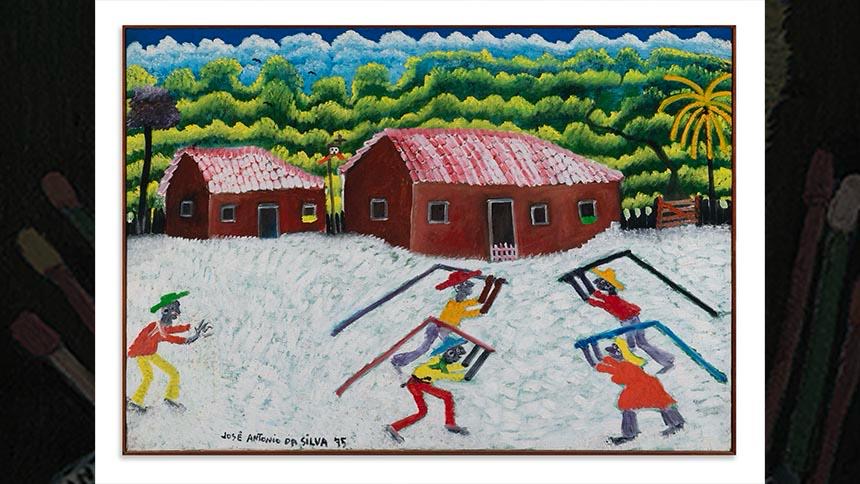

Although he explored different styles, even producing paintings with an almost abstract inclination, such as Algodoal (1972), he remained faithful to his themes and rural origins. The exhibition, by organizing the route into thematic axes, helps the visitor to perceive more clearly both his aesthetic interests and the recurrence of certain subjects.

Silva painted religious scenes, scenes of rural life, oxcarts, and popular festivals. His Brazil is far removed from the coastal imagery and idealized nature that often circulates as the country's official image. This attachment to his origins extended beyond painting.

To affirm these beliefs, he released two LPs, both titled "Record of the most authentic folklore of Brazil," bringing together compositions of his own authorship. Attentive to the transformations in the countryside, he also painted on his canvases the arrival of machines, chainsaws, burnings, and the felling of trees for the expansion of monocultures — as in "Algodoal com troncos decepados" (1975).

Although some critics have tried to categorize him as belonging to the realm of "popular art," the capacity for synthesis, the compositional rigor, and the chromatic intensity of his paintings unequivocally place him within the field of modern art. It is no coincidence that he received the nickname—as revealing as it is reductive—of "the Brazilian Van Gogh."

“Brazilian modernism incorporates the popular, the indigenous, and Afro-Brazilian art,” Pitta observes. “It’s a sui generis modernity, a kind of strategic universalism. To tell the public that modern art is art, they say, ‘look, all this you’re seeing here is art.’”

In a video from the exhibition, the artist asks: “Who is Silva?”. He himself answers: “I am Silva”. The phrase doesn't sound like a provocation, but like a statement of fact. José Antônio da Silva never had any doubts about his identity, nor about the place he believed he occupied in the history of Brazilian art.