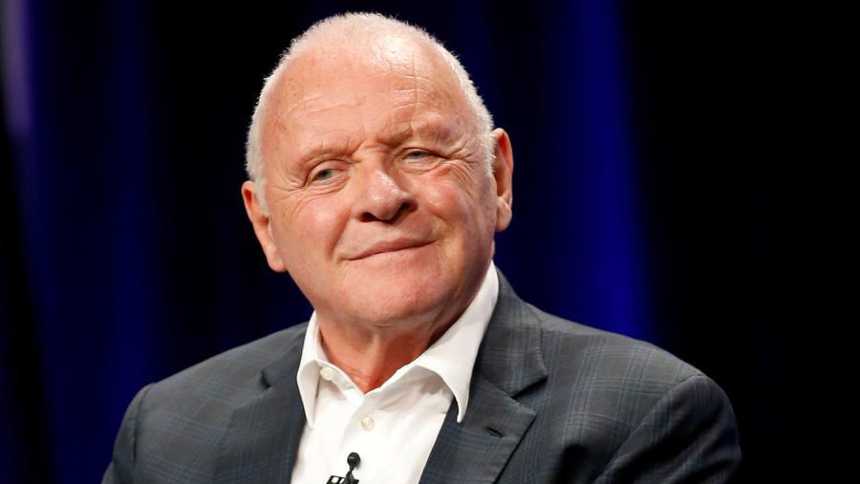

Towards the end of an eight-month run of the play Madame Butterfly in London's West End in September 1989, English actor Anthony Hopkins was, according to his own description, nearly dying of boredom. One morning, before the matinee, he went to see the film Mississippi Burning , starring Gene Hackman, and left thecinema thinking: “I would love to make a big Hollywood film. I wondered if that would ever happen. Probably not.”

Hopkins had filmed a "minor" project with Mickey Rourke, No Escape , and when his fellow heartthrob grabbed him too forcefully by the neck in a particular scene, he pushed him away and said, "Lean on me like that again and I'll glue your face to the back of my skull!" The line was real; it wasn't part of a rehearsed script.

A few days later, on a Thursday afternoon, he received a call on the theater's phone. “I have a script here in the office,” said his London agent, Dick Blodgett. “It’s interesting. Want to read it?” he asked. “What’s the film about?” the actor asked. “It’s called The Silence of the Lambs . It’s going to be directed by an American, Jonathan Demme. He’s good.” Hopkins added: “ The Silence of the Lambs . Is it a children’s film?”

Hopkins, as is well known, not only accepted the role when he learned he would be acting alongside Jodie Foster, but his performance altered the course of his destiny, earning him an Oscar and placing him in film history.

At 42, only those who had seen the delicate and sensitive Never Saw You, Always Loved You , from two years earlier, could remember one of his films. Years later, he would win his second Oscar for My Father , in 2020, which cemented his name on the list of eleven Hollywood actors to win the Best Actor statuette twice.

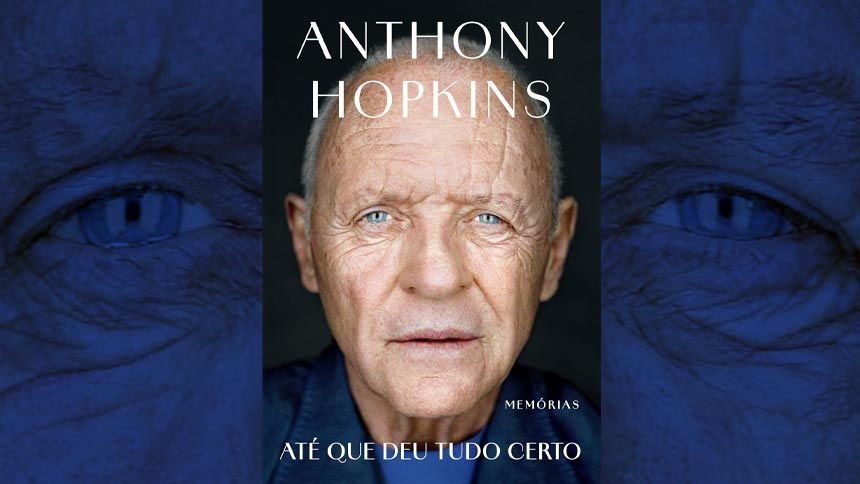

This episode, which Hopkins describes in his autobiography , Until Everything Worked Out , being released in Brazil by Sextante, follows the tone he used to recount his life.

There are two common ways to write about oneself in autobiographical format: that of the predestined and that of someone who overcame all the greatest odds against them. He chose the second.

And this choice makes all the difference, because the book presents a moving account of why he had every reason to fail in any professional career. Starting with school, where his mediocre performance almost drove his parents crazy. And he had no qualms about exposing himself in this regard:

“That strange feeling of being lost, of not knowing how to deal with anything, has stayed with me for many years of my life. I am surprised to still be here. There is no explanation,” he writes, shortly before turning 88.

As a child, his nickname on the street was "Elephant Head," because he seemed too big and disproportionate to his frail body. His parents – a baker and a homemaker – thought he had hydrocephalus and took him to a renowned pediatrician, Dr. Bray, who reassured them: he just needed to gain some weight.

After trying to encourage the boy's learning in several schools, they had no choice but to enroll him in a boarding school, West Mon, even though it strained the family's finances. This only worsened the drama of a boy who, each day, sought a way to endure existence, isolating himself from a world that did not wish him well and mistreated him in every way.

Hopkins was beaten in the street, at home, and at school, where beatings by teachers were part of the learning process. “The more I was beaten, the more I adopted my survival trick, a look of pure, stupid insolence. This look demonstrated my passive indifference to everything hostile around me,” he wrote.

Until the night he and his classmates gathered in the boarding school auditorium to watch Hamlet (1948), starring Laurence Olivier, considered the greatest Shakespearean interpreter in cinema. “I had never felt an impact like that. It was explosive. I still couldn’t understand the structure of Hamlet and its nuances.” He added: “I cried, overwhelmed by the epic portrayal of flawed fathers and mothers.”

Since then, cinema has given meaning to his life. However, it would take decades for him to land his big break, as he commented after reading the script for The Silence of the Lambs . Until then, he made a name for himself in theater, following the advice of Professor Christopher Fettes of the Royal Academy, where he studied: “Just keep learning, keep going. Don’t worry. Just go. Know that you’ll never be perfect. Just do the best you can.”

His first screen appearances were small or supporting roles, often in historical productions, where he was valued more for his diction, presence, and technical skill than for charisma or commercial appeal. Hopkins describes this period as professionally erratic and emotionally confusing, without the feeling of building a solid film career.

In the book, he attributes his delay in achieving prominence to three central reasons of "self-sabotage": alcoholism, which plagued him for decades. Even when he was working, there was no continuity or focus. Later, he acknowledged that he never had the profile of a charismatic star or heartthrob, something that the Hollywood system itself demanded. Finally, his dispersion between theater, TV, and film, which prevented a linear construction of a cinematic image.

The turning point wasn't solely due to *The Silence of the Lambs *, according to him. The real inflection point was internal, before it was professional: he had been sober for years and no longer sought approval, he learned to accept that he would never be a conventional star. He writes that he didn't see the role as a chance for consecration, but as a technical exercise, almost indifferent to external impact. According to the actor himself, "success came when he stopped waiting for it."

The actor preferred film because it had fewer reruns, he could travel, and the pay was good. “And I like it. You move around a lot. You don't put down roots. This film, Silence of Anything, could be interesting. Jodie Foster? It can't be bad,” he told his agent. Foster won the Best Actress award for her role as police officer Clarice, and the film also won Best Picture.

Then it was Hopkins' turn at the same ceremony: “I remember going up on stage. Kathy Bates handed me the Oscar. Apparently, I gave a speech. Later, I was told that one of the things I said was, 'Today marks 11 years since my father died, so maybe he also had something to do with this, I don't know.' Then I was taken backstage. I had gone through the whole ceremony with little or no anxiety.”

At home, he called his mother in Wales. It was four in the morning, UK time. And he asked a question, which he later called idiotic: if she had seen him on TV. “Of course I saw him. Why else would I be awake at this hour? Your father would have been proud of you. The boy from Wern Road in Port Talbot.” He just whispered: “Yes, everything turned out alright.”