The writer Erico Verissimo was 66 years old—he would die four years later—when he published, in 1971, one of the most original novels in Brazilian literature. Until then acclaimed for classics of the traditional history of his state, Rio Grande do Sul, he made the voluminous * Incidente em Antares* an enigma still undeciphered, more than half a century later, due to its literary value and the singularity of its "magical realism."

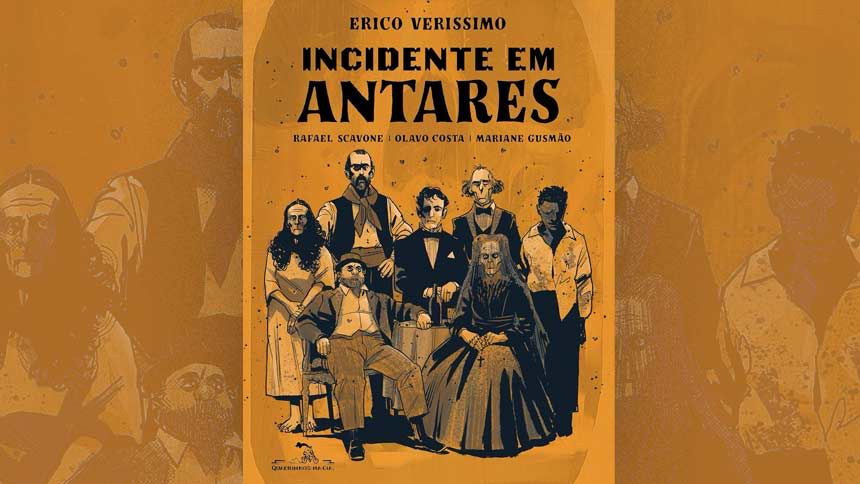

This, his last novel, has just been given a carefully crafted and skillful graphic novel adaptation, with a script by Rafael Scavone, impeccable art by Olavo Costa, and colors by Mariane Gusmão.

It is no coincidence that this mixture of macabre fantasy and political satire begins at noon on Friday, December 13, 1963, a little over three months before the 1964 military coup that deposed the president from Rio Grande do Sul, João Goulart. And exactly five years before Institutional Act No. 5, which closed the National Congress.

On that date, an assembly is convened in Antares, a small town in southern Brazil, which is completely paralyzed by a general strike unlike any seen before. Bank employees, hotel workers, café and bar staff, as well as shop assistants, refuse to return to work unless their demands are met.

“An end-of-the-world atmosphere hung over the city. Antares, in short, seemed about to be besieged by a relentless enemy,” Verissimo narrates.

No matter what the mayor does for the desperate, even threatening to order shootings at the strikers, it's all in vain. The biggest problem, however, is at the cemetery. Seven people have died in the last 24 hours and need to be buried.

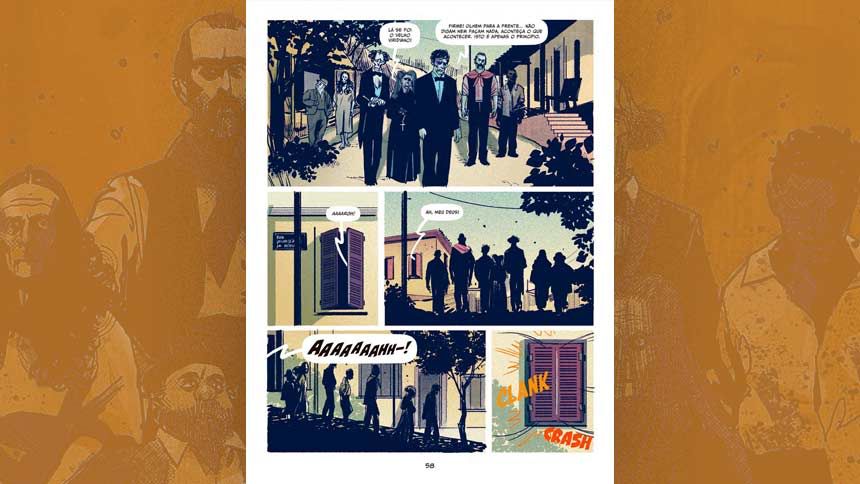

But the gravediggers refuse to do this because they are on strike. When night falls, however, the dead leave their coffins and begin to wander freely through the streets, with the audacity to pry into other people's privacy and say whatever they please, without fear of repression from the authorities.

Among them are the richest woman in the place, a suicide victim, and a black man tortured to death because of his political convictions. Another is a corrupt lawyer who comes to represent the group in their quest for a basic right: immediate eternal burial. This situation, in the early hours of the morning, serves as a pretext for a heated discussion between the living and the dead about class struggle, social differences, hypocrisy, honesty, greed, avarice, and other cardinal sins.

And when day breaks, the creatures begin to settle their scores with family members and the malevolent authorities of Antares. These authorities gather, amidst the putrid stench that pervades the city, to convince the dead to return to their coffins and await the end of the strike. But the rebellious dead take refuge in the city's bandstand, ultimately making the entire population their audience.

Both the novel and the graphic novel are not just an adventure for those who like zombies and the undead—something Verissimo certainly drew inspiration from in cinema, especially after the worldwide success of George A. Romero's 1968 film *Return of the Living Dead *. The novel is, above all, a political satire of a Brazil reduced in its ills to an almost small, rural village.

The comic book narrative works well because it doesn't have excessive excerpts and transcriptions from the original text, so common in comic strip versions of novels. The dialogues and descriptions are balanced by engaging drawings. Everything is very faithful and, in the end, the impression is that perhaps there is no more perfect novel in Brazilian literature to be explored in this way: as a graphic novel.

As writer Sérgio Rodrigues observes in the afterword, Incident in Antares is a fundamental work not only for its courageous challenge to the dictatorship, during the height of the AI-5 decree, but also for representing a kind of final assessment of the author's career.

The book, he writes, consciously condenses the main themes and procedures that have marked his career: satire, the oscillation between comedy and drama, and the vocation for direct dialogue with a large audience.

The story of the dead struggling to be buried — one of the earliest examples of "zombies" in literature — is not escapist fantasy, but a powerful political allegory, Rodrigues points out.

Set on the eve of the 1964 coup, "The Revolt of the Corpses" exposes, with corrosive humor, the hypocrisy, violence, and inequalities of Brazilian society as a whole. "The dead, freed from social conventions, reveal the truths that the living try to hide," it says.

For Rodrigues, the strength of the novel lies in the humanity of its characters, never reduced to types, even among the living: from the torturing police chief to the murdered student, all emerge full of contradictions.

“This ability to transform historical and moral reflection into engaging 'stories' has often been overlooked by critics, but it is precisely what explains Erico's enduring connection with his readers,” he observes.

The excellent comic book adaptation by Scavone, Costa, and Gusmão happily captures the spirit of the book, simplifying the dense plot without losing the political and emotional power that Verissimo intended.

With its fast-paced script, expressive art, and vibrant or subdued colors, this graphic novel makes it seem as if Incident in Antares was always destined for the world of comics as well, according to Rodrigues. It's as if Erico Verissimo returned, from the bandstand in the town square, to speak directly to the reader.