Tokyo — During the pre-production of Little Amélie , filmmakers Maïlys Vallade and Liane-Cho Han grew tired of hearing that their source of inspiration, the book The Metaphysics of Tubes , was "unadaptable" for film. The duo themselves even doubted that they would be able to translate into images the autobiography of the Belgian writer Amélie Nothomb, who, at the age of two, believed she was God.

Yes, right at the beginning of the work, Nothomb describes how she believed herself to be the center of the universe in her early years. Initially, she describes herself as God, because she feels an absolute satisfaction, like someone who doesn't need to absorb anything, like a tube—hence the title. The girl only decides to open herself to the world, allowing herself to marvel at all of creation, after tasting a piece of white chocolate from Belgium, discovering pleasure.

“The first thing that really struck us about this book was its point of view, bringing a child’s perspective on the human condition, from birth to the age of three,” said French director Maïlys Vallade during the 38th Tokyo International Film Festival (TIFF-JP), which was covered by NeoFeed .

“And we were only able to illustrate the experiences of the first years of life, many of them laden with symbolism, by resorting to the language of animation,” said Liane-Cho Han, also French, on the stage of the Kadokawa Cinema, where Little Amélie had a special screening in the Japanese capital.

One of the best animated productions of 2025, the film, scheduled for release on January 29th in Brazil, delights audiences wherever it goes. Winner of the audience award at Annecy, the world's largest festival of the genre, Amélie is competing this Sunday, January 11th, for the Golden Globe for best animated feature.

And it is also expected to receive an Oscar nomination in the category, in the announcement that the Hollywood Academy will make on January 22nd. At the Annie Awards, considered the Oscars of animation, the title received seven nominations, including best film and direction.

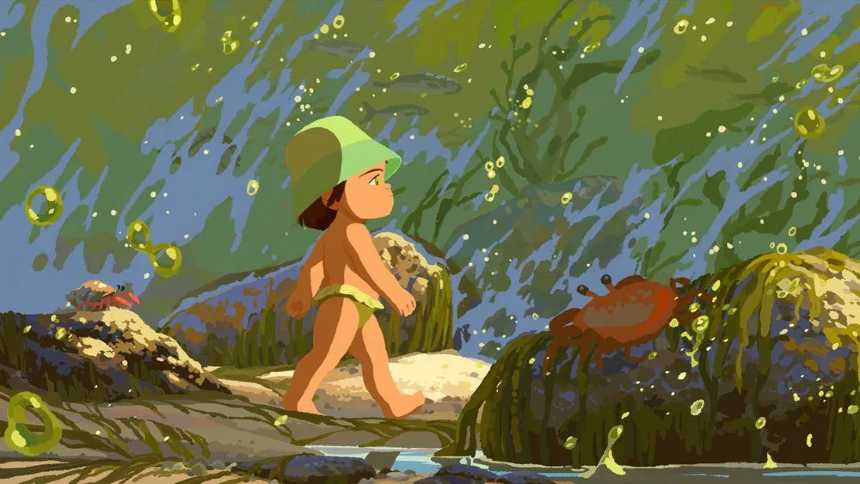

The strength of Amélie lies precisely in capturing the curiosity, wonder, and imagination of a young child. And in a way that only animation can achieve, through the possibility of taking more liberties in terms of realistic representation, and also being able to make liberal use of colors and visual metaphors.

What also works in the film's favor is the fact that it's not about an ordinary "child." Here are the childhood memories of Amélie Nothomb, one of the most awarded French-language writers of today.

She received the Grand Prix du Roman from the Académie Française in 1999 for Fear and Submission , the Prix de Flore in 2007 for Neither Eve nor Adam, and the Grand Prix Jean Giono for her body of work in 2008, among other accolades.

Nothomb is also one of the most prolific authors in the language. Since 1992, when she debuted on the literary scene with Hygiene of the Assassin at the age of 26, she has published practically one book a year, with novels generally among the bestsellers and translated into many languages. Her body of work already includes almost 30 books.

His style is known for combining simplicity in writing, with short sentences and direct prose, with thematic depth, preferring to address death, loneliness, and existentialism. And everything, almost always, is constructed on the border between fiction and reality and portrayed with humor, highlighting the absurdity of the situations.

In the case of The Metaphysics of Tubes , published in 2000, there is an additional layer, as Nothomb addresses the issue of culture shock in childhood. Although she is a Belgian national, she was born in Kobe, Japan, the daughter of a diplomat who worked primarily in the East.

This explains how little Amélie in the film initially discovers the wonders of being alive in rural Japan in the 1960s. The shock caused by an earthquake and the delight of white chocolate pull the little girl from her celestial, yet vegetative, state, finally allowing her to join mortals.

Amélie discovers what death is with the passing of her Belgian paternal grandmother, from whom she received her first white chocolate. And she herself almost drowns during a family outing on the beach, which forces the child to deal with the harshest aspects of existence.

Because she spends a lot of time with the housekeeper, who is Japanese, the girl absorbs much of Japanese culture and philosophy. And the influence of the country where she lives grows stronger, without her yet understanding what it means to belong to a family of foreigners or having the chance to first understand the Western lifestyle and mentality—since she only has contact with her Belgian parents and grandmother.

“The book allowed us to address serious issues such as identity, death, and grief, which is not common in animations based on early childhood,” said Vallade, noting that the most difficult part of the adaptation was finding a balance. “Although we were inspired by an adult book that deals with childhood, the challenge was to make a film for all generations by structuring it with multiple layers,” she added.

While younger children are initially captivated by Amélie's adventurous spirit and the colorful natural imagery of Japan, adults appreciate certain historical peculiarities. One of these is the hostility suffered by the Belgian family (and by Westerners in general) in post-World War II Japan.

“Even so, the fact that Japan lost the war to the West doesn’t prevent Amélie from receiving valuable life lessons from the Japanese governess, even though the latter lost her family in the conflict,” Liane-Cho Han pointed out. “Our film doesn’t aim to resolve war traumas, but perhaps the friendship between the little girl and the governess can teach us something in today’s turbulent world.”