New York — The poster is a reference to the classic New York message: “I ❤ NY”. But the red heart is missing. The absence of the icon is intentional, to create a sense of surprise.

This is one of the advertisements from the advertising campaign that has been circulating for a year in the city's transportation system, including subway cars, through which 4 million people pass daily. Created by the advertising agency DeVito/Verdi, the slogan is direct: " Life. Pass it on, " emphasizing that one donor can save up to eight lives.

In the first three months of the campaign, the agency also spread messages across social media, billboards , newspaper pages, and mobile digital panels that roamed New York City by car. Around Christmas time, they created memorable pieces like "The best gift is secondhand" or "A gift someone is dying to receive."

The campaign generated unprecedented traffic to the website of the advertiser, LiveOnNY, a federally designated organ procurement organization (OPO) for the New York metropolitan area.

In the United States, more than half the population has already declared themselves as organ donors on their identification documents. However, only two out of ten patients admitted to city hospitals are listed as organ donors.

To draw attention to what is one of the lowest organ donor rates in the country, DeVito/Verdi created another message: “Only 20% of New Yorkers are organ donors. Sadly, the rest will take them to their graves.”

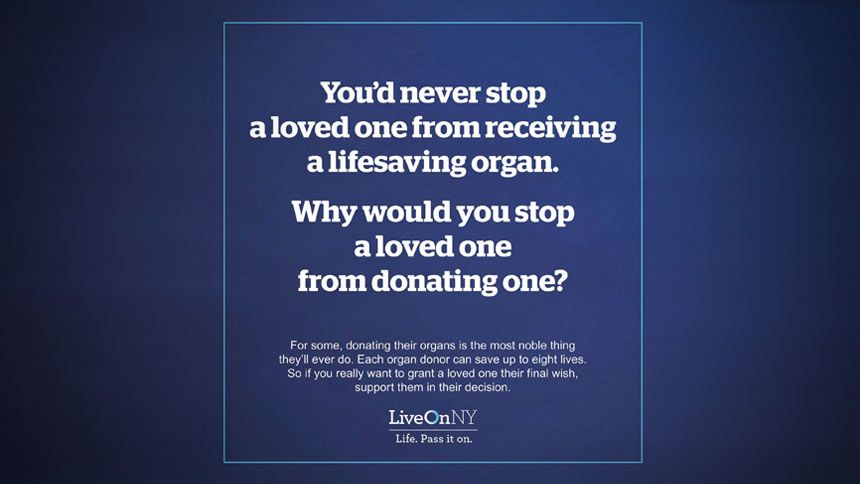

For the remaining 80%, the decision rests with the bereaved family. And, to that end, the campaign features another poster: “You would never prevent a loved one from receiving a life-saving organ. Why stop them from donating one?”

With this, the agency covered the main bottlenecks in organ donation. Currently, there are about 100,000 people on the national waiting list for an organ, 8,000 of them in New York.

Founded in 1978, LiveOnNY works with donor hospitals and transplant centers, serving a population of 13 million. In addition, agents educate the public and healthcare professionals on the subject, promote donor registration with Donate Life, and oversee the recipient list.

After the pandemic, the organization created a community engagement program through education, focusing on communities with low donation rates, such as Black and Asian communities, and also collected insights from people who became donors.

The goal was to balance donations and transplants among diverse communities and ethnicities. The initiative resulted in a 50% increase in donations between 2021 and 2024. Starting last year, it launched an advertising campaign on New York's public transportation system to reach even more potential donors.

According to the advertising agency, the campaign's impact quintupled the number of organ donations from hospitals and increased the number of organ donors and recipients in New York's Black and Asian communities by 60%.

In Brazil and Spain

In Brazil, the National Transplant System, created in 1997, is considered one of the best-functioning health programs in the country.

“This system guarantees rigorous criteria, transparency, and fairness in organ distribution, making it virtually impossible to jump the queue,” says Eduardo Rocha, professor of nephrology at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, in an interview with NeoFeed .

"The success of organ donation depends on adapting to the culture, health infrastructure, and governance of each country. We need an organized health system, continuity, and quality information, including the participation of the mainstream press, recounting success stories," he adds.

In Brazil, the approach to families is central to the donation process. Here, there is no option to register the wish to donate in official documents. Regardless of the desire expressed during life, the final decision always rests with the family, following notification of the potential donor's brain death.

Rocha says that a well-executed approach significantly increases the acceptance rate, even in delicate situations.

“The differences between donation models are directly linked to each country's healthcare system. Spain leads the world ranking in donations, and the system is organized by the government through the National Transplant Organization,” explains the doctor, who has worked in that country and also in the United States.

In Spain, hospitals do not require family consent for donation, but they still do so out of respect for the family.

The internationally used metric is the number of donors per million inhabitants, calculated annually. This allows for comparisons between regions within a country and also between countries with different healthcare systems. In Spain, there are 50 donors per million inhabitants. In the United States, this number is 44 per million.

“In Brazil, the organ donation program is linked to state governments. The state coordinator is appointed by the Secretary of Health, who is nominated by the governor. It is a political position. When organ donation is not seen as a priority because it 'doesn't win votes,' the program loses momentum and donations decrease,” he warns.

This helps explain the significant heterogeneity of donation rates in the country. "There are Brazilian states with performance similar to that of Spain, such as Santa Catarina and Paraná, exceeding 40 donors per million inhabitants, while others remain with rates close to zero," he says.

The nephrologist points out that, unlike in the United States, where OPOS professionals work outside of hospitals, in Spain they work day and night inside hospitals, with 70% being doctors and 30% being nurses, resulting in high performance.

Between 2011 and 2014, Rocha was the general coordinator of the State Transplant Program (PET) of the State Health Secretariat (SES) of Rio de Janeiro. During this time, he imported American and Spanish models, creating a hybrid model for the city.

"Hospitals with greater donation potential now have coordinators available 24 hours a day in their units, monitoring ICUs and emergency rooms," says the doctor.

“Hospitals with less potential for organ donation have begun to be actively monitored by a state center that acts as an organ procurement organization (OPO), making daily contact and sending teams when necessary. This change has significantly increased the notification of potential donors,” he celebrates.

The result was surprising: in 2008, the rate in the city was 4.4 donors per million inhabitants. After structural changes in the program, that number rose to 17 per million in 2014. Today, the state has around 20 donors per million.

“This is what’s called the ‘donation and transplantation cycle’,” he says. “It all starts with society: the more aware it is of the importance of organ donation, the better the system will function.”