A wave of protests in Iran that began late last year due to the 50% devaluation of the rial, the Iranian currency, along with 40% annual inflation, has turned into a popular uprising that, for the first time with real chances, threatens to overthrow nearly half a century of theocratic rule led by Shiite ayatollahs.

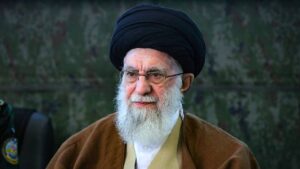

The repeated threats made by US President Donald Trump over the weekend to intervene in Iran if the government does not contain the brutal repression against the protests that are sweeping across the country's provinces have put more pressure on the regime of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei , the country's supreme leader, who, according to Trump, is "beginning to cross a red line."

"We are looking at the situation very carefully, considering some very strong options," Trump said on Sunday, January 11, aboard Air Force One, en route to Washington from Florida.

Among the options, besides a military strike, the American president cited the concern of restoring the internet, which has been cut off by the regime since last Thursday, to contain calls for protests. Trump said he would call Elon Musk, owner of the Starlink satellite broadband network, to discuss the problem.

The message was noted by the regime. On Monday, January 12, Iran's Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi stated that his country is "ready to negotiate" with the US.

“We are not seeking war, but we are prepared for it — even more prepared than in the previous war,” said Araghchi, referring to the Israeli and US attacks in June that decimated the leadership of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard , a pillar of the regime’s support, and a large part of Iran’s nuclear program. “We are also ready for negotiations, but fair negotiations, with equal rights and mutual respect.”

There are elements that reinforce the possibility of the regime's eventual fall, something attempted on four other occasions – in 2009, 2017, 2019, and 2022, for different reasons. Iran's economic crisis, the trigger for the protests, seems to have effectively reached rock bottom.

Not even oil can save us.

The US withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal in 2018 and its extensive sanctions regime have stifled the Islamic Republic's economy. Dissatisfaction with international isolation, political repression, and the theocratic regime's incompetence in managing the economy of a country that boasts the fourth-largest oil production in OPEC – approximately 3.22 million barrels of crude oil per day – and the third-largest reserves in the world (behind only Venezuela and Saudi Arabia) have exacerbated the country's problems.

According to American academic Michael Scott Doran, a senior researcher at the Hudson Institute in the US and a specialist in the Middle East, the regime has lost the most basic attribute of a functioning state: control over its currency.

“When the difference between the official and market exchange rates reaches 35 to 1, the rial ceases to function properly as a currency,” says Doran. “Savings lose their meaning, contracts lose credibility, and economic planning collapses.”

According to him, the regime now oversees two separate economies. One operates with devalued rials and sustains the formal bureaucracy. The other conducts transactions through bartering oil and hard currency, accessible only to a restricted circle of people connected to the regime.

When the Iranian Ministry of Defense had to sell crude oil directly to foreign clients to finance operations—because the central budget could no longer transfer funds through normal channels—the state lost its ability to allocate resources.

In practice, the Central Bank no longer controls Iran's foreign exchange reserves. The sanctions have forced the regime to rely on a parallel banking system, in which foreign currency is held outside Iran, deposited in shell companies and intermediaries, beyond the reach of regular state institutions.

The money exists, but it's not available for macroeconomic stabilization. For ordinary Iranians, this collapse manifests itself in daily shortages of everything. Water supplies are intermittent, even in large cities. Electricity and fuel are rationed. Food prices exceed wages, forcing families to reduce consumption and deplete their savings.

Iran's socialized economy exacerbates the problem. Fuel is sold domestically at heavily subsidized prices. Intermediaries linked to the regime buy it cheaply, export it illegally, and pocket the difference. The population absorbs the shortage; members of the regime keep the remainder. What appears to be social protection actually functions as a corruption machine.

It was against this backdrop that the protests began during New Year's week, when shopkeepers in Tehran's commercial district closed their stores, followed by others in the historic Grand Bazaar, due to the drastic devaluation of the rial after the war with Israel and the US – the currency lost half its value in six months – and the inflationary explosion.

In an effort to quell popular discontent, the regime changed the leadership of the Central Bank, appointing Abdolnaser Hemmati – who had been dismissed from his position as Minister of Economy in March precisely because of rising inflation.

On another front, President Masoud Pezeshkian – a moderate whose initiatives are sometimes overturned by the Shiite clergy – met on December 30 with representatives of trade associations, unions, and the board of directors of the Grand Bazaar, at which time he asked them to "collaborate to reduce public anxiety."

However, the participation of Grand Bazaar merchants in the protests only increased after that – which has unprecedented symbolic significance. Considered a powerful institution with a long tradition of political activism and a center for the country's wealthiest and most religiously conservative classes, it was the Grand Bazaar that, in 1978, financed Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and helped propel the Islamic Revolution that overthrew Iran's last monarch, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

“The fact that the current protests originated in the Grand Bazaar signals that even the regime’s most trusted and historically loyal supporters have turned against it,” says Iranian poet, journalist, and writer Roya Hakakian, who emigrated to the U.S. in 1985.

Hakakian observes the difference between the current wave of protests and previous ones. Those in 2009 were a reaction to fraud in the presidential election to benefit the regime's candidate. In 2017, they were mainly led by the poor, outraged by the elimination of fuel subsidies. In 2019, they were called for by residents of southern Iranian provinces suffering from water shortages. In 2022 – and in previous years – they were primarily driven by young people and university students.

“The 2026 demonstrations span generations; these distinctions have disappeared,” says Hakakian. The middle class, whose financial situation has been steadily worsening, marches alongside the poor; young people march side by side with the elderly; Kurds and Azerbaijanis protest together. “This broad social coalition explains why the current crowds are larger than any others since 2009.”

Iran's ethnic diversity, incidentally, exacerbates the problem of translating mass protests into unified political action. Persians make up only about half the population, along with large minorities of Azeris (originating from Azerbaijan), Baijianas, Kurds, Arabs, Balochis, and Turkmen, concentrated in distinct regions. These groups have different grievances and react to different pressures.

There is a way out — at least in theory. The Trump administration has put forward a clear proposal: dismantle both the nuclear and ballistic missile programs and end funding for regional armed groups. In exchange, Iran would regain access to foreign currency, stabilize its economy, and dismantle the sanctions-induced parallel system that currently fuels corruption and shortages.

Khamenei, however, rejected the proposal immediately – but there is a possibility that the gesture made to the US this Monday, the 12th, by the Foreign Minister may represent a retreat by Khamenei.

Meanwhile, international analysts are debating three possible scenarios for Iran, all of which are uncertain. The first scenario is the collapse of the regime. Prolonged unrest fragments the elite, leading to defections within the security services and a breakdown of centralized control.

The second possibility is a partial transformation. Khamenei, now 86 years old and visibly frail, could die—or be deposed—paving the way for a strongman from the Revolutionary Guard to assume power. Such a figure would adjust domestic and foreign policy to buy time. The state could survive, but the regime as we know it today would not: ideological authority would erode and institutional cohesion would weaken.

The third scenario is that of improvisation. The leadership suppresses the protests until they dissipate. The system survives without formal changes. But it emerges even weaker than before: more paralyzed, more isolated, and more dependent on force to function.

"Venezuelan exit"

Each of these possibilities carries risks. That's why a "Venezuelan option" for the Iran crisis is gaining traction. Khamenei's departure, for example, could open an opportunity for the rest of the regime to adopt a more pragmatic approach—as happened in Caracas.

“The big question is whether this would be enough to appease the Iranian population, given the level of dissatisfaction, unrest, and violence we are seeing right now,” says Ellie Geranmayeh, deputy director of the Middle East program at the European Council on Foreign Relations. “But this is a way out for the current governing system and could also be attractive to Trump and the Gulf countries.”

One worrying fact is precisely the absence of a unified opposition that could lead a peaceful transition of the regime, something difficult to imagine in a theocratic regime that has militias and a Revolutionary Guard that still believes in the religious mission of the Islamic Revolution.

The name that has emerged since the beginning of the current protests – Reza Pahlavi , son of the former Shah of Iran – is far from being universally accepted. Although hatred of the Shah fueled the Islamic Revolution, the Pahlavi heir has come to symbolize in recent weeks a lost and, in retrospect, cherished era – in which Iran's national trajectory inspired pride instead of despair.

Similarly, a revolution in Iran now would not only completely change the geopolitics of the Middle East—a process that has already begun—but would also give impetus to the populations of closed countries, such as Cuba, Turkey, and Russia, to rebel as well.

In addition, of course, it offers another trump card for Donald Trump and his new world order.